2014 Honduras Trip

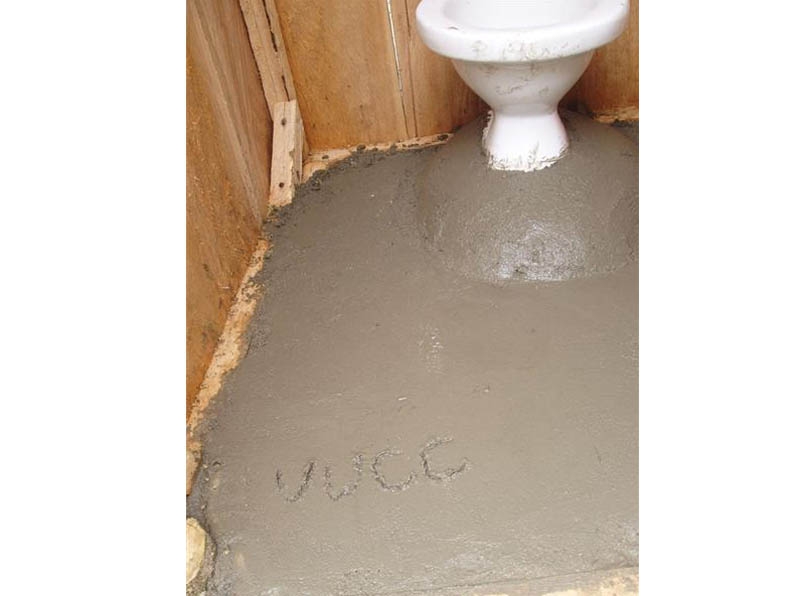

Seventeen UUCC members and friends went on the third UUCC latrine-building service trip to Honduras from June 12 to 19, 2014. The group was joined by a Honduran family (Edler, Yadira, Gaby and Alejandra) for the duration of the latrine-building time.

The group reunited with old friends and made new friends in the Cangrejal River Valley near La Ceiba, built latrines, provided health supplies, learned a lot about Honduras and Honduran culture, and witnessed both joyous and sad events. A highlight of the trip was crossing the Cangrejal River in the canasta (a hand-operated cable car) for which UUCC raised the funds.

The following photo slideshow shows people and activities on the trip. The caption of the first photo contains the names of the people.

The members of the group had deeply meaningful experiences in Honduras, and they come back knowing that there is still much to be done. They are already planning for the next service trip in 2016 or 2017.

Gabriel Gassmann (age 17) summed it up very well when he spoke the following words at the Honduras Group’s October 19, 2014 lay-led service:

As soon as you enter rural Honduras, you enter a world that somehow seems much realer than the world you have left behind. By no means do I say this to romanticize my experiences; I intend instead to do the opposite. I mean to say that rural Honduras is a place where, out of a population of only a few thousand and in the span of only a week, two babies can die, with one of those families having to sell their only means of transportation, a motorcycle, to try in vain to save their child. It’s a place where girls get attacked by the family dog and the family puts the dog down themselves. It’s a place with problems that are absolutely immediate– the long term, out of necessity, must be nearly forgotten.

This past summer’s trip was my third time going to Honduras. Each time, as I’ve aged, I’ve begun to perceive this aspect of the communities in which we’ve worked more and more. The first trip, in sixth grade, all I did was play soccer. The second time, in ninth grade, I worked but couldn’t really communicate. This time, at age seventeen, I both worked and talked, and I was treated as an adult by the Hondurans themselves. And so I learned more about what life there is actually like than I ever had before.

The man with whom I was working for the last few days, for example, was on crutches due to an injured leg. He had been sleeping by the side of a road, and a car had veered off and run his leg over. Initially, he had not gone to see a doctor, given the inconvenience and cost of such an act. The bone never fused back together– he could literally shake his leg back and forth– and so the man was now permanently disabled.

Even more shockingly, Sami, Sam, Christian and I were shown the bundle containing one of the aforementioned babies being brought back home in preparation for the burial.

The whole week, I learned like never before of the razor’s edge between life and death that these people all walk on. These stories all affected my conception of my place in the world profoundly: I realized just how mortal I myself am. Every first-world teenager believes, in some small part of their brain, that they will never die, or we at least feel completely removed from death’s inevitability.

This trip forced me into an uncomfortable intimacy with death that I had never felt before. And that sounds terrible, but it isn’t. Because the people I met in Honduras were still, by and large, kinder than me, harder-working than me, and they certainly all had a greater level of ingenuity than me.

Beyond all the dark and gloomy stuff I’ve talked about so far, rural Honduras is also a place where you can revisit a home you haven’t visited in three years – a home with nothing – and immediately be offered a cup of coffee. It’s a place where that man I mentioned earlier, crippled for life, will outwork four high school athletes. It’s a place with ridiculous levels of human potential that, in some miniscule way, we as a group are helping to unlock.

It’s a place, ultimately, where, even on that razor’s edge, humanity and goodness almost uniformly win out, and if that’s not a beautiful and inspiring fact, I don’t know what is.